Rap Song About America Enslaving Blacks Again

Martin Luther Rex Jr. had a deep respect for music as an musical instrument of change.

The March on Washington in 1963, where King delivered his "I Have a Dream" spoken language, featured live performances by Peter, Paul and Mary, Harry Belafonte, Marian Anderson, Mahalia Jackson, Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, just to name a few.

In a slice he wrote for the 1964 Berlin Jazz Festival, King had this to say most the part of music in our lives:

"God has wrought many things out of oppression. He has endowed his creatures with the capacity to create, and from this chapters has flowed the sweet songs of sorrow and joy that have allowed human to cope with his environment and many different situations."

Music clearly played a starring role in the civil rights movement. People marched to freedom songs while artists from Sam Cooke to Dylan took the bulletin to the masses in recordings equally enduring as "A Change is Gonna Come" and "Blowin' in the Wind."

Motown and civil rights:The Temptations Otis Williams reflects on life in the most successful singing group

King considered the Impressions' song "People Get Ready" the unofficial anthem of the ceremonious rights move.

Many of the songs that people marched to in the '60s have retained their relevance, with people singing "We Shall Overcome" in the streets as recently every bit 2020.

And people are still adding new songs to that folk tradition, from Lauryn Hill's "Black Rage," to Kendrick Lamar's "Alright," a hip-hop song that emerged as a popular choice for people marching for their rights at Black Lives Thing protests.

Here's a look at 20 of the most enduring civil rights songs, from the song known as the Black National Canticle, "Elevator Every Phonation and Sing," and Billie Holiday's "Strange Fruit" to Lamar's "Alright."

Best music of 2021:The top xx albums that should exist in every fan'southward drove

25. Arrested Development, 'Revolution' (1992)

These alternative hip-hop heavyweights recorded "Revolution" for utilise in the Fasten Lee biopic on Malcolm X, who earns a shout-out here aslope Marcus Garvey and Harriet Tubman, among other social activists. The track begins with a spoken dedication to "all my ancestors who were raped, who were killed and hung because of their plight for freedom and for dignity." Aerle Taree takes the get-go verse, rapping, "I have marched until my feet have bled/And I have rioted until they called the feds/'What'southward left?,' my conscience said." What'southward left is revolution. As Speech frames the upshot, "There's got to be action/If y'all desire satisfaction/If not for yourself/For the young ones."

24. The Game, 'Don't Shoot' (2014)

In response to the fatal shooting in Ferguson, Missouri, of an unarmed Blackness man, Michael Brownish, by a white police officer, the Game recruited an all-star bandage of fellow rappers to join him in this poignant protest rails. DJ Khaled sets the tone with a prayer for protection "every bit we keep our hands upwardly loftier and scream for justice." And after a fiery final poesy from Problem, who'southward tired of screaming and ready to rage, the Game passes the mic to his daughter for 1 final chorus, her immature vocalisation adding to the chilling impact. "Time to accept a stand and relieve our future like nosotros all got shot, we all got shot," she sings. "Throwing upwards our hands, don't allow them shoot us 'cause we all we got, nosotros all we got. God ain't put united states of america on the Earth to go murdered, it's murder." And then, after repeating that line about murder, she ends with a simple request: "Don't point your weapons at me."

23. Marvin Gaye, 'Inner City Blues (Brand Me Holler)' (1971)

"What's Going On" was perchance the socially relevant anthology of its era, a soulful song cycle that finds the Motown star responding to a litany of social ills, from poverty to drug abuse, environs bug and the war in Vietnam. On "Inner City Blues (Makes Me Wanna Holler)," the singer speaks directly to the economic disparity experienced by those struggling to cleave out a life for themselves in America's inner cities while questioning the government'south priorities. In the opening poesy, he sets the tone past rhyming "Rockets, moon shots" with a call to "spend information technology on the accept-nots." In the 2d verse, he sings of families sending children off to state of war as a way to brand ends meet. And before the song is through, he weighs in on the "trigger happy policing" in response to offense increasing when drastic people turn to criminal offence as solution to their economic problems.

22. Nina Simone, 'To Be Immature, Gifted and Black' (1970)

Nina Simone has said she and her musical manager Weldon Irvine hoped to write a song that would inspire young black children all over the world to feel proficient nigh themselves and celebrate their blackness. That'due south exactly what this song accomplishes, a joyous gospel tune that tells those children, "In the whole world you know there are a million boys and girls who are young, gifted and Black. And that's a fact!" Simone's vocal shares a title with a play about the life of Lorraine Hansberry, a friend of hers who wrote "A Raisin in the Sun," the starting time show on Broadway to be written by a Black woman. Within 2 years of the song'due south release, Aretha Franklin and Donnie Hathaway had both recorded their ain versions.

21. The Staple Singers, 'I'll Take You There' (1972)

This gospel-flavored funk jam finds the Staple Singers dreaming of a better place where "ain't nobody cryin', ain't nobody worried, ain't no smilin' faces lyin' to the races" with an oft-repeated chorus claw that promises to "take you at that place." In that location's really not much else to say, so they just ride the groove out, testifying their way to conservancy, performed as a telephone call-and-response with occasional breaks for instrumental solos. The song was written past Stax Records president Al Bell and inspired past the fatal shooting of his younger brother, the tertiary sibling he'd lost to gun violence.

20. Bob Marley, 'Redemption Song' (1981)

The final track on the final album Bob Marley recorded before his death in 1981, this intimate solo acoustic recording begins with a reference to Africans being sold as slaves to merchant ships. The chorus asks the listener "Won't you lot help to sing these songs of freedom?" And the second verse finds Marley referencing a speech past Marcus Garvey, urging listeners to "Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery / None but ourselves can free our minds." Similar many of the freedom songs the chorus references, "Redemption Vocal" responds to the hurting of oppression with a spiritual promise of better days to follow. "Just my hand was made potent by the hand of the Almighty," Marley sings. "We frontwards in this generation triumphantly."

19. The Roots, 'Ain't Gonna Permit Nobody Turn Me Around' (2012)

This organ-driven reinvention of the spiritual "Ain't Gonna Allow Nobody Plow Me Effectually" was the Roots' contribution to "Soundtrack For a Revolution," a 2012 compilation of contemporary artists doing traditional Civil Rights-era freedom songs (with an assist from Brooklyn art-rock legends Television on the Radio. The music video offsets black-and-white footage of 20th-century protests with total-colour clips of The Roots performing in the studio. Like many freedom song of the era, it's designed to be hands learned and sung at marches, a single refrain with slightly altered lyrics each fourth dimension it's repeated, each chorus building to the aforementioned conclusion, which in this case is, "I'm gonna keep on a-walkin', keep on a-talkin' / Marchin' on to freedom state."

xviii. Kendrick Lamar, 'Alright' (2015)

This highlight of "To Pimp a Butterfly" had emerged by the stop of 2015 as what the New York Times declared "the unifying soundtrack to Black Lives Matter protests nationwide." In that same article, Lamar told the Times he could see what the kids who were chanting his song in the streets were hearing. "Elementary phrase," he said. "Nosotros gon' exist alright. It'southward a chant of promise and feeling." Although many of the struggles he addresses in the song are on a more personal scale than systemic oppression, "Alright" is one of 3 times on the album he references the twoscore acres and a mule that formerly enslaved people were promised but didn't receive when the Civil War ended. And he touches on the root cause of those Black Lives Affair protest with "And we hate po-po / Wanna kill us expressionless in the street fo sho.'"

17. Stevie Wonder, 'Living For the City' (1973)

Stevie Wonder won a Grammy for this gritty portrait of a boy who'southward "born in Hard Fourth dimension, Mississippi, surrounded by four walls that ain't so pretty." His parents do their best to go along him moving in the right management while working hard to barely make a dollar. But the harsh realities of living for the city, where "to find a task is like a haystack needle because where he lives, they don't utilize colored people," bear witness too much for him to bear. When someone offers him five bucks to run a package across the street, he spends the adjacent ten years in jail, which leaves him wandering the streets, convinced there'south no solution. It'due south a cautionary tale that ends with a suggestion that it's up to all of united states to pause the bike of systemic poverty. "I hope you hear inside my voice of sorrow," Wonder sings. "And that it motivates you to brand a better tomorrow/This place is cruel, nowhere could be much colder/If nosotros don't change, the earth will soon be over."

16. Lauryn Hill, 'Blackness Rage' (2014)

Setting her words to the tune of "My Favorite Things" on an ominous bed of hip-hop beats and acoustic guitar, Lauryn Hill traces the roots of Black rage through American history to its tragic beginnings with "Black human packages tied up in strings." She also examines the ongoing sins of systemic oppression that continue to define the Black experience for far too many people in the age of Black Lives Matter. "Blackness Rage is founded on blatant denial," she sings. "Squeezing economics, subsistence survival / Deafening silence and social command / Black Rage is founded on wounds in the soul." When she beginning shared a lo-fi recording of "Black Rage" in 2014, it was defended to the people fighting for racial equality in Ferguson, Missouri.

15. Pete Seeger, 'We Shall Overcome' (1963)

This was one of the civil rights movement's most popular songs, an unofficial anthem and so pervasive that President Lyndon B. Johnson slipped the championship phrase into a speech to Congress in March of 1965 in the wake of tearing attacks on ceremonious rights demonstrators during the march from Selma to Montgomery. Two years prior to that spoken communication, a young Joan Baez led a crowd of 300,000 in singing the gospel song at the Lincoln Memorial during A. Philip Randolph's March on Washington. Amidst the more notable artists to have covered the song are Mahalia Jackson and Pete Seeger, who played a key role in weaving the gospel song into the cultural fabric as a song leader at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. His "Nosotros Shall Overcome" is in many ways the definitive version.

14. Fannie Lou Hamer, 'Go Tell It on the Mountain' (1963)

The original lyrics of this 19th Century spiritual celebrate the birth of Jesus. By the early '60s, both Fannie Lou Hamer and Peter, Paul & Mary were doing a version that subbed in "Let my people go" for "Jesus Christ is built-in." Hamer was deeply involved in the civil rights movement, a community organizer known for her use of spirituals who organized the Liberty Summer Project, a volunteer campaign in 1964 to register as many black voters as possible in Mississippi. Hamer'due south version of the song is a cappella gospel with Hamer's emotional testifying backed by handclaps and a joyous choir.

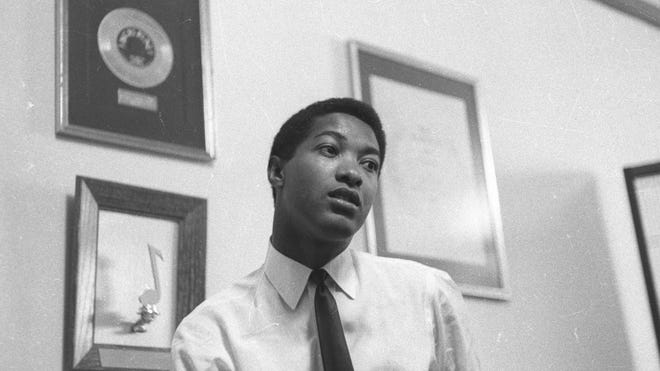

xiii. Sam Cooke, 'This Little Lite of Mine' (1964)

The earliest known recording of this gospel song of unknown origin is a field recording washed in 1934 by John and Alan Lomax of Jim Boyd at the State Penitentiary in Huntsville, Texas. It was widely used in Black churches past then and emerged as a civil rights anthem in the '50s and '60s cheers to the efforts of Zilphia Horton, Fannie Lou Hamer and Bettie Mae Fikes. Information technology's a simple proclamation of cocky-empowerment with an frequently-repeated chorus of "This lilliputian low-cal of mine/I'm gonna let it smoothen." Sam Cooke's recording on 1964'south "Sam Cooke at the Copa" is especially uplifting — joyous even — serving equally a perfect segue into the soul vocalizer'south as joyous rendition of Bob Dylan's ceremonious rights anthem "Blowin' in the Air current."

12. Gil Scott-Heron, 'The Revolution Will Non Be Televised' (1971)

More than a spoken-discussion performance set to music than an actual song, "The Revolution Volition Non Be Televised" was written in response to the spoken-word slice "When the Revolution Comes" by the Blackness Poets, whose rails begins with "When the revolution comes, some of usa will probably take hold of it on TV." Gil Scott-Heron uses that line as a starting point to argue that "Yous will non be able to stay home, blood brother" when the revolution comes. "You will not be able to plug in, turn on and cop out / Y'all will non be able to lose yourself on skag and skip out for beer during commercials." As the track goes on, he unleashes a stream of satirical pop civilisation references to illustrate the many ways in which the revolution will not exist provided for your passive amusement value, ending with "The revolution volition exist no re-run, brothers / The revolution will exist live."

xi. Bob Dylan, 'Blowin' in the Current of air' (1963)

In Martin Scorsese's documentary "No Management Dwelling house," Mavis Staples recalls her first impression of this vocal and how she couldn't understand how a young white man could write something that captured the frustrations of the Black feel every bit powerfully as Dylan does here. Sam Cooke was impressed enough to add information technology to his repertoire and wrote "A Change Is Gonna Come" in part considering he wished that Dylan'south song had been composed by a person of colour. Although the lyrics aren't exclusively concerned with civil rights — in the opening verse, Dylan sings, 'Yes, and how many times must the cannonballs fly before they are forever banned — information technology's easy to hear how it came to exist embraced as a civil rights anthem. In the opening line, he asks, How many roads must a man walk down before you call him a human?" And later, he wonders "And how many years can some people exist before they're allowed to be gratuitous?"

x. Kim Weston, 'Lift Every Voice and Sing' (1972)

Kim Weston'southward emotional reading of this life-affirming gospel song emerged as a defining moment of Wattstax, a concert held on the 7th anniversary of the 1965 Watts riots at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, where many in the crowd of more than 100,000 raised a fist in the air as she sang. The Rev. Jesse Jackson, who introduced her as "Sister Kim Weston," called "Lift Every Voice and Sing" the Black National Anthem that day. And he wasn't the showtime or terminal to call it that. Based on a verse form past James Weldon Johnson and set to music by his blood brother John Rosamond Johnson, the vocal was first performed in 1900 by a choir at a segregated school in Jacksonville, Florida, as function of a altogether celebration for President Abraham Lincoln.

nine. Public Enemy, 'Fight the Power' (1989)

This hip-hop classic was written to order for "Do the Right Matter," a Spike Lee joint from 1989 exploring racial tension in a Brooklyn neighborhood. In an interview with Time, Lee talked about how he was looking for a song to underscore the film's climactic riot scene. "I wanted information technology to be defiant, I wanted information technology to be aroused, I wanted it to be very rhythmic," he said. "I thought right away of Public Enemy." Mission achieved. Fueled by the Bomb Team'southward incendiary production, Chuck D raps almost fighting the powers that be with tossed-off references to James Brown, Malcolm Ten and their own starting time album. And before the song is through, he's trashed two paragons of white pop culture, Elvis Presley and John Wayne, accusing both of racism. He's since walked back his thoughts on Presley, saying it was more virtually the racists that anointed him the King of Rock 'n' Roll at the expense of the blackness artists who inspired much of what he did.

8. Mavis Staples, 'Nosotros Shall Non Be Moved' (2007)

"Like a tree that's planted by the h2o, we shall not exist moved." Several folk acts recorded this uplifting spiritual in the '50s and '60s, from England's King of Skiffle Lonnie Donegan to Pete Seeger and the Seekers. Mavis Staples slowed it down to dramatic effect on a deeply soulful rendition she cut for 2007's "We'll Never Turn Back," a concept album of songs related to the ceremonious rights movement produced by Ry Cooder. Similar many spirituals, its give-and-take are based in scripture, in this case, the Book of Jeremiah. In 2017, students at Howard University, a historically Blackness university, sang "We Shall Not Be Moved" to protestation quondam FBI director James Comey taking the stage to deliver a convocation accost.

vii. The Staple Singers, 'Freedom Highway' (1965)

Driven past a gritty dejection guitar lick and thundering handclap, "Liberty Highway" begins with a call to "March up freedom's highway/ March each and every twenty-four hours." And for those who may have wondered what it was that had the Staple Singers marching upward that highway each and every day, they laid in on the line in more explicit terms than most: "At that place is just one affair I can't sympathise, my friend / Why some folk call up freedom was not designed for all men." Mavis Staples revisited that highway on 2008's "Live: Promise at the Hideout," which also featured such civil rights anthems as "We Shall Not Be Moved" and "This Footling Light of Mine."

6. Nina Simone, 'Mississippi Goddam' (1964)

Nina Simone has said she wrote this song in a rush of fury, hatred and determination upon learning of four young Black girls murdered in the bombing of the xvi Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama on Sept. fifteen, 1963. It was besides inspired in role by the racially motivated murder that aforementioned yr in Jackson, Mississippi, of ceremonious rights activist Medgar Evers. The song was beginning released as a live recording on "Nina Simone in Concert," done in the style of an upbeat evidence tune, consummate with the comic aside, "This is a prove tune just the testify hasn't been written for it yet." Simone has chosen "Mississippi Goddam" her first civil rights vocal, to be followed by farther classics equally enduring equally "Four Women" and "To Exist Young, Gifted and Black."

5. Bob Dylan, 'The Times They Are A-Changin' (1964)

The championship track to Bob Dylan's most topical album was a deliberate attempt to write an anthem for the changing times, which is exactly what this vocal became. Dylan never explicitly references race in a folk vocal warning congressmen and senators, "The battle exterior ragin' will soon shake your windows and rattle your walls." But information technology captured the mood of the moment, embraced by the ceremonious rights motion, inspiring covers past Nina Simone and Odetta. In the liner notes to "Biograph," the vocalizer explained to Cameron Crowe what he was going for: "I wanted to write a big song, with brusk curtailed verses that piled up on each other in a hypnotic way."

4. Billie Holiday, 'Strange Fruit' (1939)

Ahmet Ertegun, the co-founder and president of Atlantic Records, one time referred to Billie Holiday's "Strange Fruit," a song she first performed in early 1939, as "the beginning of the civil rights movement." Written in 1937 past Abel Meeropol, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, it offers an unflinching portrait of the horrors of lynching as a form of racial terrorism, comparing the victims' bodies to a "foreign and bitter crop." Information technology's equally unsettling as it is profound and therein lies its ability, setting the scene, "Southern trees carry a foreign fruit / Claret on the leaves and claret at the root / Blackness torso swinging in the Southern breeze / Strange fruit hanging from the poplar copse." Information technology only gets darker from at that place, every bit shocking decades later as it had to be in 1939. And Vacation'southward suitably chilling commitment completes the mood.

three. James Brown, 'Say It Loud – I'chiliad Black and I'm Proud' (1968)

This Black pride anthem is somehow every chip as funky every bit it is empowering. And it is pretty damn empowering. But this is James Brown in his prime as a trailblazing funk pioneer. Of form it'southward funky, complete with a crowd-pleasing chorus set as a spirited call and response between the legend and his fill-in singers for the day, a grouping of young children. "Say it loud," he demands. "I'm Black and I'thousand proud," they respond. Brown pulls no punches here, setting the tone for the first verse with "Some people say we've got a lot of malice / Some say it'due south a lot of nerve / But I say we won't quit moving until we get what we deserve." But the record's most quotable moment comes later on, when he rhymes, "We're people; we like the birds and the bees" with "Nosotros'd rather die on our feet than exist living on our knees."

2. The Impressions, 'People Get Ready'

No lesser an authority than Martin Luther King, Jr. named this Curtis Mayfield gospel vocal the unofficial anthem of the civil rights move, fifty-fifty though the lyrics don't accost the state of race relations as explicitly equally other songs that may be vying for that title. In that location'due south a reason King so often turned to Mayfield's message of deliverance with its promise of a railroad train a-comin' to motivate his swain marchers. Whether you believe that railroad train for which "you don't need no ticket; you simply thank the Lord" is bound for heaven (the well-nigh probable destination) or a better life on earth, there's no dubiousness many listeners found information technology easy to imagine their oppressors in the poesy that starts, "There ain't no room for the hopeless sinner who would injure all mankind just to save his ain."

i. Sam Cooke, 'A Change is Gonna Come up' (1964)

Showtime performed in February 1964 on "The This evening Show Starring Johnny Carson," this civil rights anthem draws much of its timeless appeal from the ability of Sam Cooke's impassioned commitment, underscored by gorgeous orchestration. Y'all tin can experience him feeling every word. Although it only briefly touches on discrimination ("I go to the movie and I go downtown / Somebody go along telling me 'don't hang around'"), it couldn't be more than obvious what kind of change he'south after when he hits you with that gospel-flavored chorus of "Information technology's been a long, a long time comin' but I know a change gonna come / Oh yep it will." The vocal was partially inspired by an incident in which Cooke and his bandmates tried to annals at a "whites merely" motel in Shreveport, Louisiana, and partially inspired by Bob Dylan's "Blowin' in the Wind."

Reach the reporter at ed.masley@arizonarepublic.com or 602-444-4495. Follow him on Twitter @EdMasley.

Support local journalism. Subscribe to azcentral.com today.

Source: https://www.azcentral.com/story/entertainment/music/2021/01/12/best-civil-rights-protest-songs/6602985002/

0 Response to "Rap Song About America Enslaving Blacks Again"

Post a Comment